Life expectancy across the world has seen a dramatic increase since the 18th century. The emergence of preventative medicine and vaccines that minimized infant mortality, the agricultural and trade revolution, and the development of sanitation have all greatly contributed to the increase. This evolution of life expectancy had greater preponderance in developed countries.

Today life expectancy is vastly unequal across, and even within, geographies. This is demonstrated in recent Society of Actuaries’ (SOA) research showcasing the widening inequality in life expectancy between the lowest and highest socioeconomic county-level deciles within the United States. The difference in life expectancy at birth between these socioeconomic groups grew from 4.1 years to 7.2 years, and 1.6 years to 5.8 years, for men and women respectively over the period 1982 to 2018.

The concept of “democratization of longevity” refers to making longevity or “long life” accessible to everyone, in all countries and in all walks of life. Many will agree that this concept is both desirable and idealistic.

My prediction is that despite the recent widening in inequality we will see greater democratization of longevity in the future through innovations in health technology, particularly tackling three pillars: greater prevention of disease, greater affordability these new innovations, and greater accessibility to them.

A look at the evolution of life expectancy

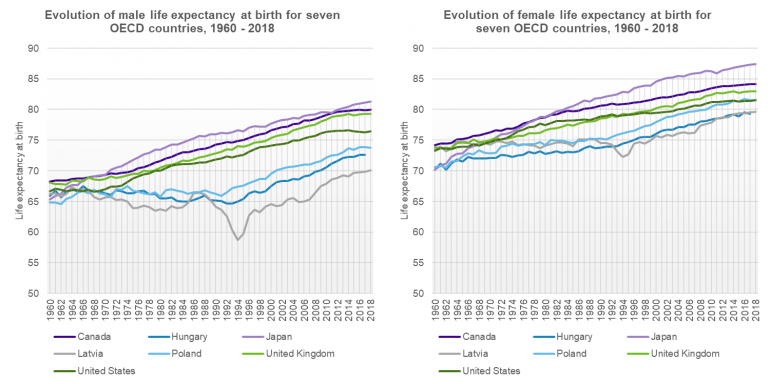

Illustrated below is the evolution of life expectancy at birth for seven Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries: Canada, Hungary, Japan, Latvia, Poland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Across the seven countries, male life expectancy at birth ranged from 64.8 years to 68.2 years in 1960, and 69.8 years to 81.1 years in 2017, demonstrating an increase in the inequality of life expectancy of almost eight years between these countries over the period. For females, the increase was approximately four years. The inequality in life expectancy is more apparent and unsettling if we consider, for example, developing countries in Africa, averaging a life expectancy of around 63 years in 2019.

Source: Data from Human Mortality Database. University of California, Berkeley (USA), and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany). URL: http://www.mortality.org (data downloaded on August 10, 2021).

Notes: Life expectancy in 2018 for Hungary was unavailable on the date of download.

Closing the gap in life expectancy will stem from innovations in health technology

My fascination with living a very long life began from a young age, but it was not until I started my career that I appreciated the sheer complexity of the factors that would impact this outcome.

First, the inequality in longevity is influenced by individual factors; those related to one’s biology, status, or lifestyle (e.g., sex, genetics, income, education, employment, and geography). Apart from one’s sex and genetics, the individual factors are largely connected to one’s life choices. The extent to which individuals adopt a healthy lifestyle can certainly improve their chances of living longer, but this is only one piece of the puzzle. The broader view is that closing the gap in life expectancy will be dependent on addressing social and economic issues affecting society such as wealth inequality and efficacy of healthcare systems.

If we address wealth inequalities between and within countries then we will increase democratization of longevity, however, this is not where I see the immediate gains coming from. With continued focus on innovations in health technology, I believe we will see further improvements in the performance and delivery of healthcare services. Technology has the potential to bring healthcare costs down and healthcare accessibility up to address inequalities. Generally speaking, if health services are of a high quality, accessible, and affordable to all, then we will have better health outcomes and a healthier global population overall.

The great equalizers?

Greater disease prevention

Many of the gains in life expectancy over the last 100 years have been credited to revolutionary vaccines against diseases such as smallpox, measles, and polio. Researchers are currently undertaking the development of a universal flu vaccine with the goal of protecting against existing or emergent flu strains which could in turn eliminate the need for an annual flu shot. This could reduce the death toll from the seasonal flu and mitigate the effects of flu pandemics.

Furthermore, artificial intelligence (AI) has transformed the healthcare space and will continue to aid in the prevention of chronic diseases. With the help of AI, healthcare professionals are already achieving more rapid and accurate patient diagnoses and disease detection.

Greater accessibility

A 2019 publication by the OECD highlighted that barriers to accessing treatment persist across countries with 20% of adults who need to see a doctor not doing so, and with even less access available to those who are lower on the social spectrum.

Telehealth has had some success in addressing physical accessibility to care by connecting doctors and patients using videoconferencing software. This provides an opportunity for people who are disabled, severely ill or geographically disadvantaged to access medical advice on demand and eliminate unnecessary travel time. The coronavirus pandemic increased the utilization of telehealth in low-income groups, and with the convenience of home care and monitoring from one’s mobile phone, we could continue to see widescale adoption in rural communities and developed countries. Telehealth has also brought forth the concept of “networked care” which involves connecting local health centers with specialist hubs of expertise, equipped with the staff and technology required.

Greater affordability

The medical advancements discussed will not have much success in achieving democratization of longevity if they are not affordable. In fact, without affordability, they can further increase the gap in life expectancy.

Fortunately, the technological era with AI, “Internet of Things” solutions, and Cloud Computing has provided an avenue for reducing healthcare costs by facilitating the completion of tasks with greater speed, accuracy, and lower resource utilization. Some examples include automation of administrative tasks and the digitization of health information and infrastructure. The health industry is often criticized for its inefficiencies and rising costs; still, there is real opportunity if there is greater adoption of new age technologies.

We should also seek more tailored solutions for those who cannot afford traditional healthcare and insurance - microinsurance is such a solution. It operates the same as conventional insurance except that it is designed to offer certain levels of coverage at very low premiums. It is specifically targeted at 50% of the world’s lowest-income households (making it relevant for up to 80% of the population in some countries).

Altogether, I believe greater democratization of longevity is achievable with the adoption of health technologies, while ensuring they are accessible and affordable. I am hopeful but I see several challenges ahead. Such a reality will be reliant on governments, health care professionals, and patients’ acceptance and reliance on what the future of health holds. It will also require global partnerships to build out ecosystems that will facilitate inclusive innovation.

What do you think?

Will we see greater longevity democratization across the globe and within nations in the future?

What do you think?

Let us know your thoughts and comments on this publication on our Friends of Club Vita LinkedIn Group