Inspired by the loss of my much-loved dad, some reflections on what we’ve learned in a generation. I’m now approaching the age at which my dad retired, but I am planning a different 7th decade.

My family’s journey

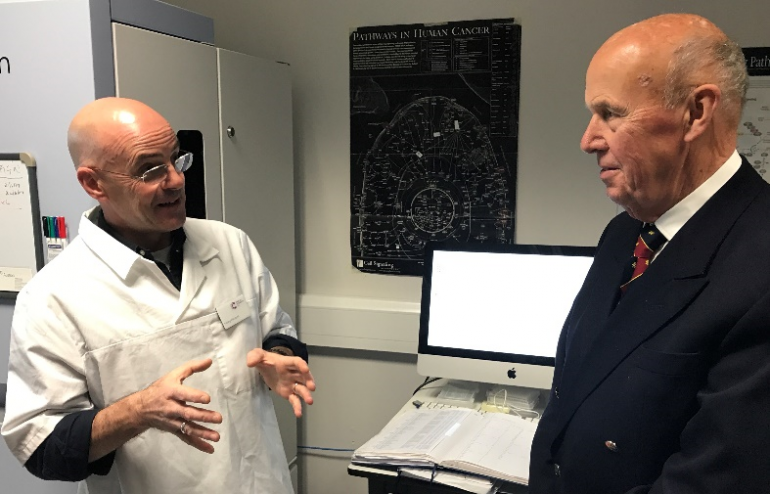

It’s now a year since my dad, John Anderson, died from Alzheimer’s disease. The photo shows him on a visit to a modern cancer research facility in 2017. My dad’s clock stopped at 85 years, but he had little recognition of close family members for the preceding two or three years.

Thirty years earlier, my granny (my dad’s mum) had succumbed to the same fate.

My father’s professional interest

My dad worked as a neuropathologist, so, given his mother’s illness, it was natural that understanding dementia would be a passion of his. No doubt, he was worried that there could be a genetic link.

Since my dad was studying dementia in the 1980s, the UK population has aged, and Alzheimer’s and dementia has become the most common cause of death.

So, what have we learned in the space of a generation?

Although we still lack a treatment, our understanding of the risks of dementia has certainly progressed. I’ve observed three notable advances.

1. Dementia is only rarely inherited

The best news is that the new field of genomics – the digital mapping of the human genome - has enabled us to eliminate genetics as the cause in most cases. According to the UK's Alzheimer's Society, “in the vast majority of cases (more than 99 in 100), Alzheimer’s disease is not inherited.” Phew! (please excuse my selfish sigh of relief.)

Instead, the finger is being pointed at the way we lead our lives, rather than the genes that we are born with. According to the US's Alzheimer's Association, “experts agree that in the vast majority of cases, Alzheimer's, like other common chronic conditions, probably develops as a result of complex interactions among multiple factors, including age, genetics, environment, lifestyle and coexisting medical conditions.”

Heard this all before? Yes, it’s pretty much the same advice as for reducing your personal risk of from cancer and heart disease. It turns out that the same things that keep your heart healthier for longer (regular exercise, healthy diet, moderation in alcohol, not smoking) are good for protecting your brain too.

So, the mantra is all about investing in prevention, rather than cure. A healthier lifestyle will reduce your risk of the three biggest killers. That’s quite a return on investment.

But that’s easier said than done. How do we encourage sustainably healthier lifestyles? That takes me to an advance in my own field of actuarial science.

2. Life insurers have developed dynamic long-term policies

As I approached my 50th birthday, I celebrated by buying myself a “modern” life insurance policy. Yes, that’s sad, but true.

Despite life insurance contracts often lasting 30 years or more, traditionally the price was set once at the outset, and then not touched. That may sound as if it protects the insured against future hikes in premiums, but the design failed to proactively encourage the customer to stay healthy.

The modern designs, pioneered by Discovery, initially in South Africa, have several features that align my personal interest with that of the insurer. For example, in linking my premiums to the healthiness of my lifestyle. And the proceeds of my policy would be paid early if I get diagnosed with dementia (helping to pay for decent care in my final days).

Premiums are reviewed annually, enabled by activity trackers in a similar way to telemetrics in car insurance. The insurer’s incentives encourage me to get out of breath at least three times a week, through a mix of running, cycling and circuit training sessions. Comparing myself with my dad, he was a keen golfer: he had a lovely touch around the slick greens of St. Andrews. But a round of golf only raises your heart rate modestly. My dad, and few in his generation, would have thought about doing regular weights sessions in the gym so they could drive the ball further down the fairway.

3. Lifelong learning is rewarded

Finally, successive advances in neuroscience in the last thirty years have shown that the brain can continue to be trained beyond childhood.

In my dad’s working days, the accepted wisdom was that our brains did not change after childhood. Perhaps that belief reinforced the then culture that learning was a thing that young people did, and that we would follow a three-phase serial life of education, work and then retirement.

This excellent blog discusses the benefits of lifelong learning. It introduced me to the concept of neuroplasticity and that, in turn, led me to this video of an amazing panel discussion of four experts in neuroscience from the World Science Festival in 2019: The Nuts and Bolts of the Brain: Harnessing the Power of Neuroplasticity.

I found myself glued to this video for a full hour, something that rarely happens. The video brought home to me just how much technology had improved – for example in brain imaging – and the sheer volume of research in neuroscience. My key learning was that new pathways can be developed in the brain after childhood – as shown by successful therapies on stroke patients. Old dogs can learn new tricks.

Consequently, one of the other experts’ recommendations to avoid dementia is to learn new skills. According to Harvard Health, going back to school is better than memory games. The idea being to stimulate those synapses in your brain, creating new neural pathways.

For example, there is some evidence that bilingual brains are more resilient to dementia. For the last five years, I have been learning a second language, in my case, French. I’ve found this pretty tough, not helped by having impaired hearing. However, my digital French dictionary makes my life easier than old paper dictionaries: it enables me to repeat the pronunciation until I “hear” the word properly. And I’d like to think that the fact that it is tough, is what makes it good for your brain: you have to think harder and be more determined to put in the hours. Even if it fails, there are great compensations: learning a new language provides a great route into new cultural experiences.

So, today’s received wisdom on delaying the onset of dementia is that once you have mastered a new skill, go learn a new one: variety is the spice of life.

Club Vita’s brain training for later life health

At Club Vita we are passionate about promoting later life health. We usually focus on financial health, helping a wide range of institutions improve the stability and security of retirement income by effectively managing longevity risk. But mental and physical health are just as important for long and happy retirements. Inspired by our learnings on the prevention of dementia, in 2022, members of the Club Vita team are challenging themselves to learn something new.

Personally, I’m going to try to learn to swim free-style properly. The coordination of arms, legs and under water-breathing is something I never mastered as a child. To keep me focussed, I have signed up for a 1500m open water swim next September: it’s the first phase of a triathlon, which will be another first for me.

What skill have you always wanted to learn but lacked the motivation to find the time? Why don’t you join us?

Lang may yer lums reek!

Douglas

Meet the team

Club Vita could not deliver the vast array of statistical insights without our gifted team.