With coronavirus COVID-19 all over the news, how might a global pandemic impact on life expectancy, and what are the implications for pension schemes?

28 February 2020

There’s been lots of chat over the past few weeks on coronaviruses, and in particular the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) variant that first surfaced in Wuhan City in China and has now spread to every continent except Antarctica.

Coronaviruses are actually fairly common. They typically cause respiratory problems, including pneumonia. While the majority of those who contract coronavirus will recover, those with weakened immune systems, older people, and those with existing long-term health conditions like chronic lung disease can have more serious issues, in some cases fatal.

In today’s highly connected world, where news (not to mention rumours, speculation and misinformation) can go global in seconds, it’s easy to feel somewhat alarmed by the onslaught of stories. But just how bad could it get, and how could it impact pension schemes?

We start by looking back at lessons from history.

Spanish flu

The most serious pandemic in modern history is the so called ‘Spanish Flu’, a particularly virulent variant of the influenza A virus (H1N1) which devastated the global population over 1918 and 1919.

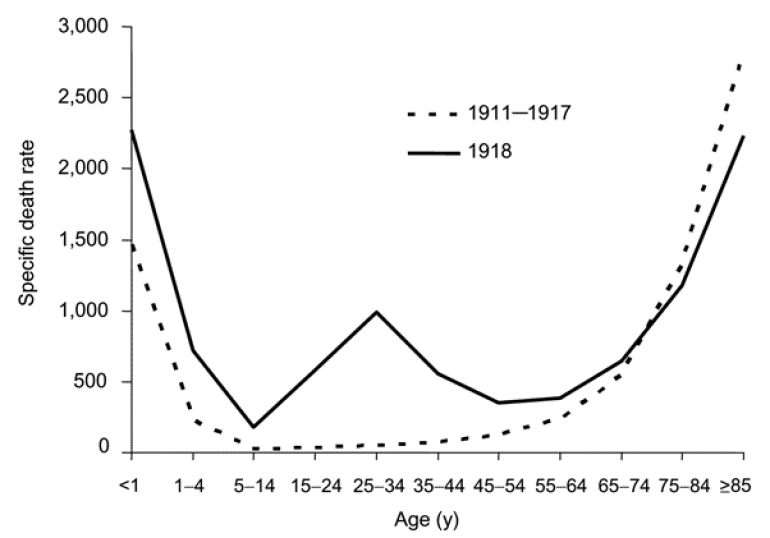

While typically influenza is mainly a risk to the very young and very old, the Spanish Flu also struck down otherwise healthy 20-40 year olds (the chart below shows mortality rates in the US by age)1.

While it’s hard to be precise, given recording practices at the time, and limited testing, it is estimated that Spanish Flu infected around 1/3 of the world population, and caused up to 50 million deaths globally (some estimates put the death toll at as much as 3% of the world population).

Despite this, it was decided to reconstruct the virus in 2005 for research purposes!

COVID-19

While little is known about the specific COVID-19 strain at this stage, it is likely that it is spread through contact. Simple steps like using a tissue when you cough/sneeze and washing your hands thoroughly are likely to help prevent spreading infection.

At time of writing (27th February 2020), there have been 82,411 confirmed cases, resulting in 2,808 deaths and 32,971 have recovered (see here for the latest figures).

The mortality rate is currently estimated to be around 2.3%. However, it’s impossible to be definitive about mortality rates at this stage. There is likely be underreporting of infection rates, particularly for those who exhibit mild (or no) symptoms, while we don’t know how many of those currently infected will eventually die.

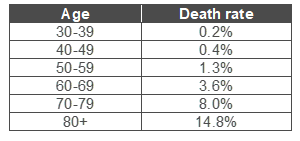

Looking at the age profile (with the same caveats as above), we see probabilities of death (after contracting the virus) in line with the table on the right. This shows the much greater impact on the elderly, with a significant jump in mortality rates for those aged 70+ (although only 12% of the cases in the study are in this age band). Interestingly, while the number of confirmed cases is similar, death rates for men are markedly higher (2.8%) than for women (1.7%). And unsurprisingly, those with no pre-existing conditions are much less susceptible – with a death rate of 0.9%.

What this might mean for pension schemes

Clearly there are great number of unknowns at present. While the UK has seen just a handful of cases so far, the experience of Italy shows that pockets can appear suddenly, and it’s possible that contagious carriers may not always display symptoms, making virus containment much more difficult.

But what if we wanted to explore an extreme scenario, assuming similar infection levels as Spanish Flu at 1/3? Based on the death rates shown above for those infected, we might see an 80% increase in deaths over the year, leading to a dip in life expectancy at 65 of as much as 4-5 years.

How might this impact on mortality assumptions? If we were to view it as a one off ‘shock’, it may well be that we don’t actually adjust assumptions at all. Care would need to be taken in calibrating both base mortality rates and future improvements, potentially stripping out the ‘extra’ deaths. Going forward, we might expect the following year to see (very) strong improvements, given the improved average health of the surviving population.

The bigger impact for pension schemes may well be the reduction in their pensioner populations – which will have a direct impact on both liabilities and scheme cashflows. The impact will be dependant on the scheme maturity, with the biggest impact on the most mature schemes. Assuming an overall 2.3% mortality rate and a 33% infection rate, liabilities could reduce by up to 1%. However, if the scheme was concentrated in the 70-79 band, the reduction could be as high as 3%, while liabilities for the 80+ could reduce by almost 5%.

While schemes would ‘benefit’ from the lower pension payments, there may be liquidity issues as a result of a surge in death lump sums. Not to mention the myriad of other issues around asset values, as well as broader concerns such as employer covenants etc.

Hopefully the above scenario won’t come to pass, but pension schemes would do well to consider how well prepared they are to face such scenarios.

1 Taubenberger, J. K., & Morens, D. M. (2006). 1918 Influenza: the Mother of All Pandemics. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12(1), 15-22. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/arti...

Pandemic Panic?

Download a print friendly version of this article.