22 May 2017

Two recent pieces of research really move on our understanding, taking the lengthy investigation in an unexpected direction.

Since the 1960s, public health research has suggested that differences in lifestyles (smoking, drinking, diet and exercise) explain much of the variation in postcode longevity. Of course, these statistics are merely saying that the habits of people living in certain areas are associated with low or high life expectancy, and don’t prove beyond reasonable doubt that the habits are necessarily causing the variation in life expectancy.

In addition to lifestyle, I have long wondered how big an effect the genes we inherit from our parents could have on our longevity. In other words, how much of a helping hand did the genetic lottery bestow on the long-lived?

1. Your genes at birth have little impact on your longevity

Exhibit one comes from the advancing frontier of genetic research, where microbiology meets mathematics. The technology revolution that has turned the sequencing of the human genome into an everyday industrial process is revealing previously untold secrets. By looking at how longevity runs in families, geneticists have long believed that a small part could be attributed to genes, the rest being due to lifestyle and ever-present chance, but only now are researchers beginning to pinpoint which genes matter. The research of actuary-turned-geneticist Dr Peter Joshi at Edinburgh University is showing that inherited faulty genes already linked to a small number of nasty diseases like lung cancer, are affecting lifespans, but as yet do not explain all the genetic differences in longevity between different people within the same community. At the same time, he has also shown that genetic variants that increase educational levels also increase lifespan. Here's a taster of Peter's work.

My take-away – as someone modelling longevity for portfolios of pensioners - is that a higher proportion of the variations in longevity outcomes are now known to come from things that happened after birth than was previously believed. That takes us to the second fascinating nugget, again coming from the exciting new world of genomics.

2. The accumulating damage to your genome is greater for those with unhealthy lifestyles

Exhibit two comes from a new book about how things called "telomeres" in our DNA affect the speed of our body clocks. It suggests that the pace at which our DNA ages as we live our lives – the biological “rusting” of our bodies as cells renew – is related to the healthiness of our habits. The suggestion is that those who look after their bodies with the same tender care as the owner of a priceless vintage car can slow down their ageing process.

This may not come as a shock, but association is now turning into causation, with the fundamental research on the genome explaining past public health observations. When combined with the news that the genes we are born with have little influence on lifespan, I feel like a nagging doubt has been removed. I feel more in control of my own destiny and it gives me more motivation to invest time in staying healthy.

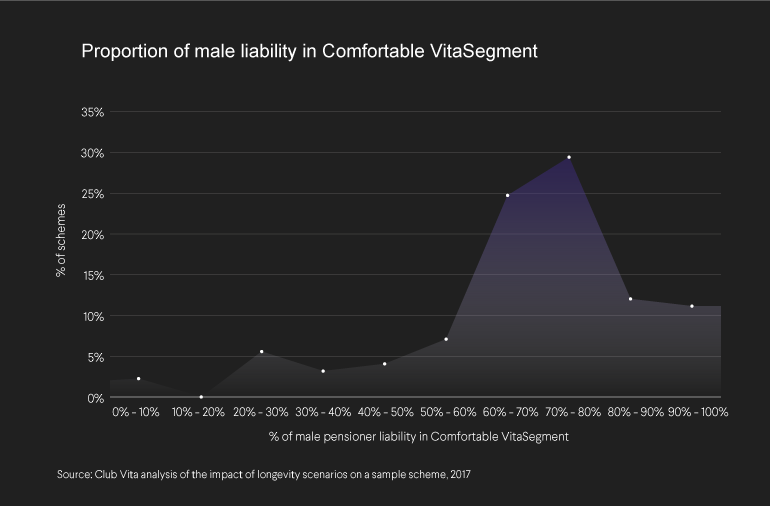

Both areas of research illustrate why stratifying populations along socio-economic lines is the sensible thing to do when managing the funding of diverse portfolios of pension liabilities. Within the UK Club Vita family of 200+ plans, the average plan has 70% of its liabilities in the Comfortable group, but there is a wide range from close to zero to almost 100%. Movements in the national population average are simply not representative of what’s going on in the liabilities of pension plans. We would expect similar results to be true in the USA.

Find out more

Find out how our unparalleled insights can benefit your plan